For over 15 years, productivity has been attacked by two major enemies: absenteeism on one side and presenteeism on the other, each trying to have the highest impact on organisations’ direct and indirect costs. And recently, we saw the arrival of a third enemy, ‘leaveism’. Despite it all, this war is anything but lost as several strategies exist to reduce the costs associated with lost productivity.

Absenteeism in Switzerland and in Europe

We all know absenteeism. In Switzerland, as well as in many countries of the European Union, the hours of absence correspond to the time when a person is not at work, when he/she should normally have been there, due to illness, accident, maternity leave, military or civilian service, or for personal and / or family reasons, or even bad weather conditions. Holidays, public holidays, and absences due to flexible working hours are not considered absences (Swiss Federal Statistical Office, 2019). In Switzerland, absenteeism rates vary from 2% to 5% depending on the economic sector.

It does generate direct annual costs of CHF 4.2 billion for the Swiss economy, according to a study commissioned by the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs SECO. We can add the indirect costs (loss of productivity, disorganization of the team, delays and deterioration of working conditions) which are between 3 and 5 times higher than the direct costs.

In Europe, a study by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions estimated that absenteeism could cost around 2.5% of GDP. This would represent a total cost of absenteeism of $ 470 billion in the European Union alone, more than double that of the United States. And again, this is only the tip of the iceberg.

And what about presenteeism?

Presenteeism is a term defined in opposition to absenteeism to characterize a situation where an employee is physically present at work when his/her physical or mental state does not allow him/her to be fully productive. The employee considers that being on sick leave is a sign of weakness, and for fear of losing his/her job or responsibilities, he/she comes to work ignoring his/her physical and psychological symptoms.

Allow me here a distinction between the concept of presenteeism in France or in Anglo-Saxon countries. The term was originally used in the UK to describe the problem of employees coming to work when they were not physically or mentally in good condition and did not consider any ‘motivational’ factors. In France, this insidious and difficult to diagnose ‘occupational disease’ has two faces.

- Over-presenteeism, which involves staying at work, and even working overtime, while you are totally exhausted or sick. It is similar to chronic over-engagement motivated by various reasons: personal values associated with work, perfectionism, company culture, excessive workload, fear of losing one’s job, etc.

- Contemplative presenteeism (or moral absenteeism) which means being present at work but not actually working. It can be due to too much suffering at work or a lack of motivation.

This extension of the concept – the motivational factor – is now also used in Anglo-Saxon countries to include employees who are disengaged and not quite “present” in their daily work.

Presenteeism can be fatal, and not just due to the costs

Presenteeism is extremely harmful for employees’ health, promoting the appearance of certain pathologies that can, in the worst case, lead to death. The Japanese use the term “karoshi” or death from overwork to designate the death of executives or office workers by cardiac arrest, stroke or even suicide following extreme workload, lack of sleep and excessive stress. In 2017 alone, according to a Japanese government report, “karoshi” claimed 191 lives, while the police reported that same year some 2,000 cases of suicide for professional reasons. Meanwhile, the Japanese Ministry of Labor registered more than 1,500 compensation claims related to deaths caused by overwork. And while the data varies, the problem remains significant. In fact, it has dramatically increased in recent years.

Strategies to reduce such deaths vary but appear to be futile. Some employers try to force their staff members to leave work early; but even by turning off the routers and the lights, workers continue to accumulate overtime, mainly for financial reasons since wages are very low. One in five Japanese works more than 80 hours of overtime per month. 80 hours of overtime per month is considered to be the threshold above which there is an increased risk of dying, according to the standard on working hours of the International Labor Organization (ILO / ILO).

What is particularly surprising is to see the emergence, in Japan, of a new profession: Expert in Working Hours Reduction, as well as bonuses for workers who sleep more than six hours. I don’t think we’ll ever need that kind of encouragement to work less in this part of the world, but we never know.

How is presenteeism measured?

Today in Europe, and with the extraordinary situation we experience since the outbreak of COVID-19, rates of presenteeism seem to have increased. Who would have thought that working from home during lockdown would not solve presenteeism’s issues? In the UK alone, almost half (46%) of Britons working remotely during lockdown said they felt more pressure to be ‘there’ for their employer and colleagues, and more than a third (35%) say they continued to work although they did not feel well.

This obviously has a cost. While we do not yet have exact figures for presenteeism rates during and after confinement, we do have data from a few years back showing that presenteeism rates can be up to 4x higher than absenteeism’. These ratios are articulated by the Institute for Employment Studies in their report 507 published in 2016. On average, based on several studies conducted on the subject, it is estimated that the rate of presenteeism is 2-4 times higher than the rate of absenteeism.

However, it remains difficult to estimate the prevalence of presenteeism in the workplace or to quantify the loss of productivity. Despite this, there are measures, such as the Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) of the WHO or the Work Limitation Questionnaire (WLQ) developed by Debra Lerner, PhD and the team of researchers at the Health Institute of Tufts Medical Center in Boston, USA. The WLQ measures functional health related to work. It indicates how often physical or emotional health issues prevent employees from functioning effectively. We use this specific questionnaire in our HRA (Health Risk Assessment), which allows us to quantify the financial impact of lost productivity linked to presenteeism and absenteeism.

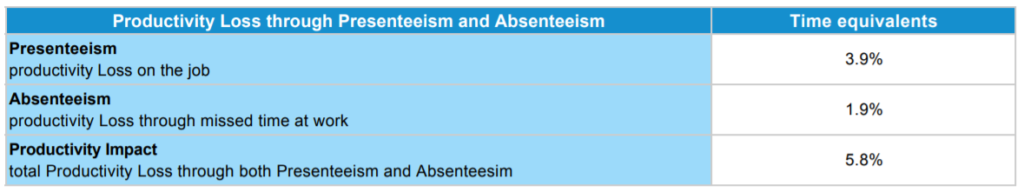

To give you an example, you can see below part of the HRA results of one of my clients, including their productivity loss. What is interesting to see is that their presenteeism rate is equivalent to 2x their absenteeism rate.

Our HRA goes even further by quantifying the financial impact of lost productivity based on an average annual salary of US$ 50,000. With such a result, my client pays US $ 2,900/per employee in lost productivity, including $ 1,950 in presenteeism alone. When we know that my client has more than 2000 employees, I’ll let you do the math. But how to reduce such presenteeism rate remains the question…

How to fight these outrageous presenteeism costs?

First of all, look out for warning signs within your teams and your organization. Here are a few that should grab your attention:

- Employees who are always tired and catch all seasonal viruses without getting fully sick

- Decreasing productivity, not reaching objectives which have already been reduced

- Absenteeism rate lower than average, for no valid reason

- Decreasing engagement and motivation rates

- Overtime on the rise, for no valid reason

And then, here are four steps that should allow you to reduce your costs of presenteeism, while decreasing those of absenteeism at the same time:

1. Rethink your corporate culture

As with any topic of corporate culture, it starts at the top of the pyramid. Are members of your management committee role models for their teams, do they take time off when they are sick, do they allow themselves to take vacations and disconnect? Here is a little anecdote about one of my clients. The organization that appointed me had a presenteeism rate approaching 7%, and the HR Director I was in contact with wanted to put in place a health strategy to improve the situation. Imagine my surprise when, after coming out of an emergency room due to decompensation, he returned straight to the office, without even going home first!

Does your corporate culture encourage or even reward overtime, work on weekends and during holidays, not disconnecting, not taking vacation, coming to work when not feeling well? I’ll let you answer these questions in all honesty. You will see, addressing toxic culture concerns will have a real impact on your rate of presenteeism, and therefore on your productivity.

2. Measure your absenteeism and presenteeism rates

Yes, it is possible to measure, as we demonstrated it above. Invest in the right measurement tools and carefully monitor how those metrics change over time to see if and how your actions are affecting your rates.

3. Develop a health and wellbeing strategy

Key elements of your strategy could include, but not be limited to: a work & leave policy encouraging flexible hours, taking vacation, limiting overtime, an Employee Assistance Program (EAP), priority on caring and supportive behaviours of managers, training on warning signs of exhaustion, etc.

If you want some inspiration on how to put together a wellbeing strategy, read our 10-step strategy for implementing an effective health culture.

4. Implement clear and caring absence management

Absence management policies that focuses solely on sick leave only provides a partial picture of the productivity losses related to employees’ health. What is crucial is to spot and treat the illness beforehand, when the employee is at work but not doing well, and we have already spotted what we call in French ‘absences perlées’ or ill-health. Then, once the employee is absent, it is important to stay connected during the sick leave. And the final step, called therapeutic return to work, is crucial for the success of the whole process. These three steps should ideally be the responsibility of an occupational health nurse, which would allow medical secrecy, ensure a ‘healthy’ culture of absence, which in return would strengthen a culture of trust and therefor reduce the rate of presenteeism.

I obviously cannot end this article without mentioning the ‘third enemy’: leaveism. This term was coined in 2013 by Dr Ian Hesketh, a researcher at the University of Manchester in England, to describe the phenomenon of employees, too sick to work, who use flexible hours, their annual leave such as their vacation, their days off and other leave entitlement schemes to recover from their illness rather than taking sick leave. Hesketh subsequently extended the definition to include occasions when employees took work at home and / or on vacation that they could not accomplish in paid work hours. This term is also associated with a negative impact on employee mental health as well as productivity issues. Although it represents a whole new feature of academic literature (mainly in the UK), UK HR managers and executives report a high level of awareness of leaveism in their organisations. For example, 37% say employees use their time off when they are not well, 57% say their employees work overtime, and 33% say employees use time off, like vacation, to catch up. (CIPD, 2018).

If your motivation is to decrease your absenteeism rate for cost reasons, rethink your strategy. And if presenteeism isn’t on your radar, then make sure you it put on. Ensure your culture encourages and values well-being and compassion, your managers’ behaviours encourage their teams not to hide their discomfort, and that they understand the relationship between absenteeism and presenteeism. And remember that employees have the right to be sick, and indeed, they should even be encouraged to take sick leave when necessary. The more they feel ‘free’ to announce their illness, without it having an impact on their career and responsibilities, the more you will be able to reduce these exorbitant presenteeism costs, and this obviously without increasing the rate of leaveism.